Looking Back on How the Parks and the Climate Have Changed Over the Past 100 Years

Publication Date

Image

Story/Content

Two weeks ago, the National Park Service celebrated its 100 years in action. Here at the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy we commemorated the occasion with a picnic with our partners and park allies, the National Park Service and the Presidio Trust. In between burgers, cake, and friendly chatter, we had a number of presentations by park leadership representing these three organizations. One of the pervasive themes running through many of their speeches was the topic of climate change. At one point, the audience was asked to think about the founders of the Park Service and what they might have predicted their idea of the parks would look like in a hundred years.

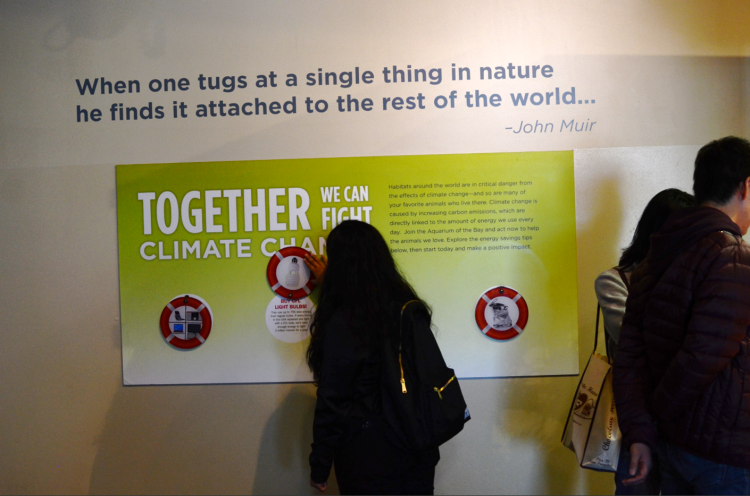

We hear so much about tipping points in the climate conversation and it got me thinking that this centennial is a symbolic tipping point and an opportunity to re-envision many of the roles of parks and public lands on the issue of climate change. In a recent interview Director of the National Park Service, Jonathan Jarvis, stated that “fundamentally, [climate change is] the biggest challenge the National Park Service has ever faced.” Undoubtedly, it is a threat to the cultural natural resources that make American parks special; however, parks have a unique opportunity to serve as living laboratories for addressing this problem. Parks also benefit from dedicated staff who are trained communicators, many of whom are becoming educated on this issue and are using their parks as a venue through which to talk about climate change in a way that provides this issue with a physical, personal context that visitors are interested in. In the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, for example, park staff no doubt emphasize that sea level rise could harm many of our coastal resources from Lands End to Crissy Field.

It’s no secret that acceptance and action on climate change has lagged in the United States. It’s amazing to think that prior to 2009, the National Park Service’s parent agency, the Department of Interior, did not have a formal policy on climate change. However, given this bumpy start, it’s amazing to see how far we’ve come. The National Park Service now has a number of strategic plans to address climate change, offers trainings on climate science and communications, and provides overall support across the service through its Climate Change Response Program. While this commitment to addressing climate change is laudable, many park interpreters face challenges in discussing this issue at their park sites. The reasons range from worry over visitor reaction (particularly negative reaction) to a lack of information on local, place-based climate impacts.

The good news is that many of these challenges are remediable. Communications specialists and social scientists are churning out new research regularly on tips and tricks for communicating on climate change which park staff can take back home to their sites. This includes focusing on clear, concise messages, giving visitors actions that they can take to address this issue, and infusing the conversation with personal stories as opposed to just statistics. Perhaps most importantly, a recent survey showed that most park visitors would like to receive information on climate change at the parks they visit; 91% even stated that they would change their behaviors in the park or refuge they visited to mitigate climate change.

We’ve come such a long way since President Woodrow signed a bill in 1916 mandating that the National Park Service conserve the cultural and natural resources within the parks and ensure that they are both enjoyed by the public and preserved for future generations. Now we are grappling with new, 21st century challenges such as how to make sure park provide welcome environments for the changing racial makeup of the United States as well as how to tackle human-caused climate disruption, which still has many unknown impacts. Luckily, our national parks are making brave efforts to discuss and address these issues head on.