Being Seen - Homelessness in Parks

Publication Date

Story/Content

In January, I went to a workshop on homelessness in parks hosted by the National Recreation and Park Association. After a rich panel discussion, one homeless advocate shared a bit of wisdom that is still sticking with me. He remarked that our communities have a lot more compassion for the homeless, and thankfully, it’s no longer socially acceptable to treat homeless folks with disdain. Yet many of us still haven’t developed a healthy approach or view of the homeless. Instead of disdain we disassociate, becoming quite skilled at distancing ourselves from our homeless neighbors. Now we avoid eye contact, ignore their greetings, and refuse to acknowledge their presence. Sitting in a conference room of 60 people, I felt a wave of heat go up my spine. He was talking about me. I ignore the homeless.

He went on to say that homeless folks often internalize being ignored. He argued that ignoring our homeless neighbors robs them of their dignity; of their humanity. Later on in the workshop, his point was validated by two women who were once homeless living in parks. They shared their story, and both of them told of being ignored and avoided, and then later becoming experts of hiding, of being unseen. For both women it took someone seeing them to jump start their journey out of homelessness. One woman, who struggled to manage her schizophrenia while homeless, remarked that it was the first person who talked to her that convinced her to seek support and services. It was a beautiful moment, witnessing two women who spent years being invisible in parks, now speaking in front of a room of park professionals from across the country – advocating so that other folks might be seen.

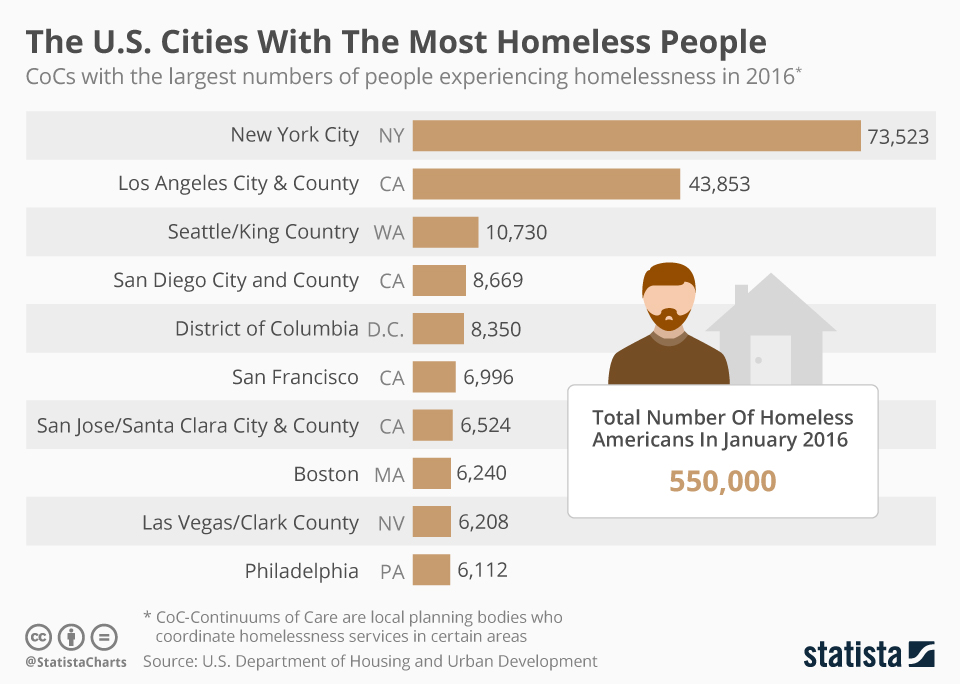

Now that I’ve had a little time to process all the information from the workshop, I’m wondering what cost parks pay for disassociating from the homeless. It might be robbing us of our agency. How can we attempt to solve, or at least improve, what we refuse to see? What if parks are more powerful, more skilled, and better advocates than we imagine? Considering that only a minority of homeless individuals are chronically homeless (15% by the latest estimates), what if the problem isn’t as scary and unsolvable as we dismiss it to be? To put it another way: if you knew there was an 85% chance that any homeless person would find housing within a year, would it change how you saw them?

I, too, was resigned that the homelessness crisis was hopeless, but now I feel empowered. What an exciting time to work with parks! I’m anxious for all the new solutions and partnerships that might come from really seeing our homeless neighbors. It feels much more honest and brave to tackle this head on. Who knows? Parks might really be powerful.