Parks Are for Everyone

Publication Date

Image

Story/Content

This is my park. This is my park. This is my park.

The founder of Outdoor Afro, Rue Mapp, taught me this mantra. Outdoor Afro often has first-time hikers or nervous campers chant “this is my park” before new wilderness experiences. Claiming belonging is a powerful tool in their work of cultivating nature connection with African Americans. I’ve borrowed this phrase from Outdoor Afro, using it when I’m a lone brown face in a green space.

This is my park. This is my park. This is my park.

This year I’ve gotten to explore our local and national park system more than ever before. My increased connection to this land has increased my understanding of its African American heritage and history. I already knew about the Buffalo Soldiers who, 150 year ago, were some of the original caretakers of these shores, meadows, and forests. This history is a source of comfort and pride for me and has spurred my curiosity about the other black folk that have walked and served on this land. I recently gathered another lesser-told story I’d like to share with you: a story of the pivotal role the Sutro Baths played in California’s journey towards civil rights.

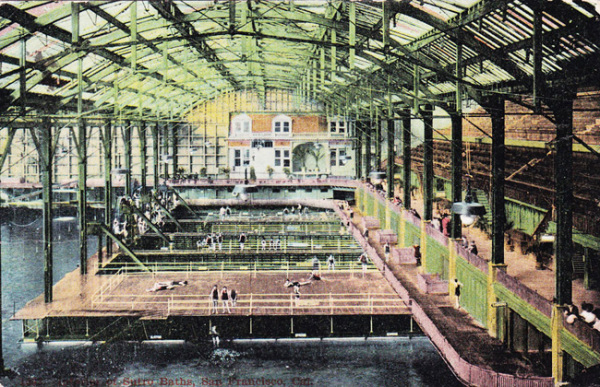

On July 4th and July 11th of 1897, John Harris, an African American, was denied entry to the Sutro Baths, a bath house, swimming, and recreation area located by the Cliff House. Now a part of Golden Gate National Parks, the Cliff House and Sutro Baths were once privately owned by Adolph Sutro, former mayor of San Francisco. The Sutro family contested that their white customers would not “co-mingle” with other races in their pools and that discrimination was necessary to avoid financial ruin.

John Harris and the Sutro Baths made headlines when Harris sued Adolph Sutro. His case is notable because Harris won and, most importantly, gave teeth to California’s first civil rights law, the Dibble Act of 1897. Passed only a year after Plessy v. Ferguson legalized “separate but equal,” the Dibble Civil Rights Act mandated that Californians “of every color or race whatsoever” are “entitled to the full and equal facilities of all places of public accommodation.” The Dibble Act was the precursor for the better known Unruh Civil Rights Act of 1959, which ultimately served as a model for the nation’s Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Harris v. Sutro, was the first test of California’s commitment to civil rights and it was set right here in the Golden Gate National Recreational Area. The legacy of Henry Clay Dibble, author of the Dibble Act, is also tied to park land. Dibble, a champion for civil rights and women’s suffrage, is buried in the San Francisco National Cemetery.

I want to thank author Elaine Elinson and my new office buddies from the National Park Service, Steve Haller and Abby Sue Fisher for sharing this piece of history with me. As we kick off Black History month our park professionals, historians, community partners, culture-keepers, and educators are working hard, as they always do, to remind us that parks are for everyone.

Oh – and pools, the coast, and ski slopes are for everyone, too.

This is my park. This is my park. This is my park.